Controlling the Campaign Narrative

See how the candidates, special interest groups and news outlets compete to get their narrative of the campaign heard — and evaluate the value of seeking multiple sources of information about the candidates and their campaigns.

Get even more great free content!

This content contains copyrighted material that requires a free NewseumED account.

Registration is fast, easy, and comes with 100% free access to our vast collection of videos, artifacts, interactive content, and more.

NewseumED is provided as a free educational resource and contains copyrighted material. Registration is required for full access. Signing up is simple and free.

With a free NewseumED account, you can:

- Watch timely and informative videos

- Access expertly crafted lesson plans

- Download an array of classroom resources

- and much more!

- Current Events

- Elections

- Politics

- 6-12

- College/University

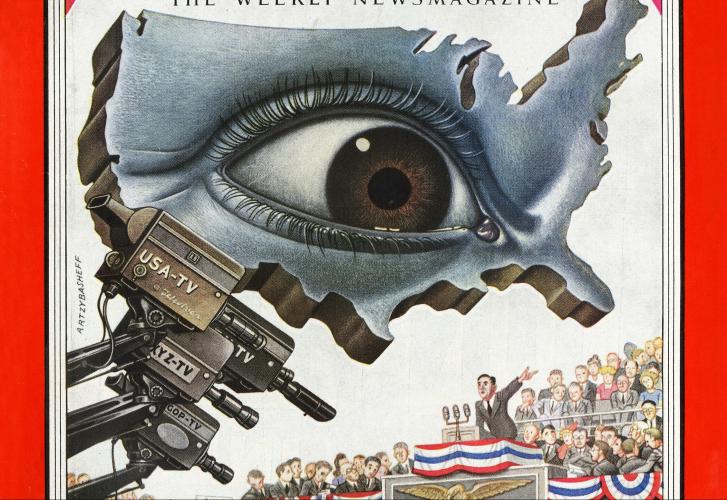

In 1952, both national conventions aired on television for the first time. Time magazine explores the effect of this momentous evolution in news and technology.

- Ask students how they hear about campaign news? What sources do they use for updates on the candidates and election events?

- This case study is one of four in the Campaign Messages section of the EDCollection that looks at communication strategies in speeches, news coverage, ads and all-encompassing campaign trail events. Explain that the case study they will be looking at will raise questions about the strengths and weaknesses of each source for the public.

- Read the Explore the Debate question aloud and/or write it on the board. Read them the overview that sets the scene for group work. Tell them they will use historical and contemporary examples to reach a consensus in small groups on an answer to the debate question.

- Pass out copies of the case study and the Organizing Evidence worksheet. Have the groups read each of the four Election Essentials and use the Questions to Consider to help guide the discussion. They should complete sections 1 and 2 on the worksheet.

- Have the students look at the Pages From History artifacts for the case study on NewseumED.org and complete section 3 on the worksheet. Give the groups 15 minutes to collect and organize information to formulate evidence-supported arguments for their answer to the debate question. (If time is an issue, skip the artifacts or assign as homework.)

- Ask the groups to share their conclusions and reasoning. You may want to use the Questions to Consider again to push and expand the debate.

- Copies of the case study handout, one per student (download)

- Organizing Evidence worksheet, one per group (download)

- Access to NewseumED.org case study artifacts

- NewseumED Pinterest board of related resources (optional)

Where can voters get information about the candidates, and how valuable is each option?

Thomas Jefferson wrote, “An informed citizenry is at the heart of a dynamic democracy.” But becoming informed in today’s media landscape is not a straightforward process. From blogs to TV networks to the candidates’ own tweets and email blasts, there is no shortage of information about the presidential race. The challenge is not where to find out what’s happening in the campaign, but how to know which sources can be trusted and for what purposes.

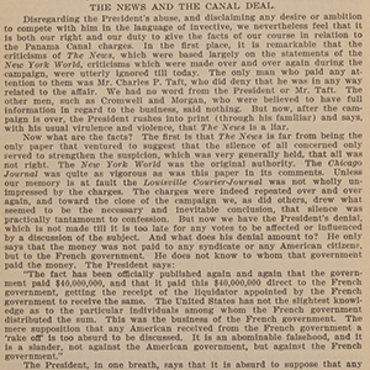

1. Can You Trust Newspapers?

In the early United States, newspapers were both the primary source of all news and the mouthpieces of political parties. For example, in 1800 a Federalist newspaper supporting President John Adams’s re-election bid reported that if rival and Vice President Thomas Jefferson became president, “In a short time, licentiousness and immorality would meet with the most public approbation … and men would … [become] infamous debauchees, assassins, cheats, thieves, liars." Such brash attacks became less common as party-controlled newspapers faded near the end of the 19th century. Today, most mainstream news outlets have codes of ethics that guide staff into separating news from opinion, but logistical challenges or personal biases still have the power to creep in and color what news is reported and how.

2. New Media, New Perspectives

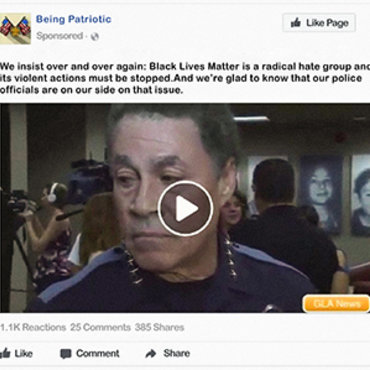

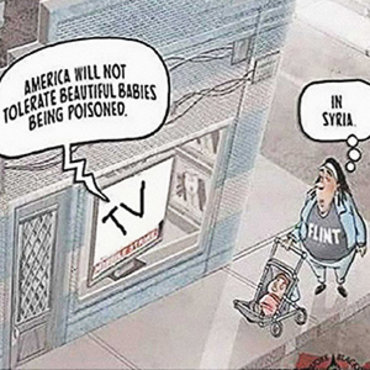

Print newspapers are no longer the only — or even the primary source — of news. In fact, 67 percent of U.S. adults in 2017 reported getting at least some of their news from social media, up 5 percentage points from a year earlier. Half of U.S. adults said they often get news from television (local/network or cable), compared with 43% who often get their news online (news websites/apps or social media). This increase in digital news consumption allows diverse sources to bring attention to smaller campaign events, shed new light on a topic and add new perspectives to the conversation. But many are produced by untrained journalists or are for a niche audience, leading to incomplete or agenda-driven reporting.

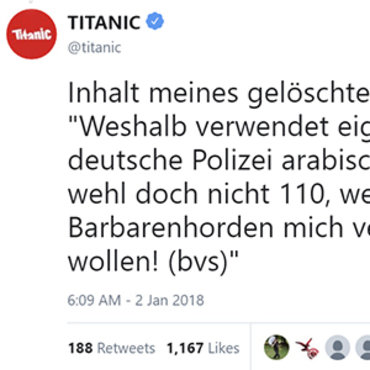

3. From the Horse’s Mouth

Presidential candidates — and their campaign teams — now use social media to bypass traditional news media to take their messages directly to voters. It allows them to get personal, control the content and avoid cross-examinations, though a growing number of fact-checking operations put statements to a truth test afterward. In 2008, 2.9 million people signed up to get a text message from presumptive Democratic nominee Barack Obama announcing his running mate. Major news organizations broke the news before most people got the text, but the candidate still benefited, according to Nic Covey with Nielsen Mobile. "The value of the message goes far beyond the 26 words and 2.9 million recipients," he said. "Here, Obama branded himself as cutting edge, inflated the already enormous press attention paid to his VP pick and further established a list of supporters’ most coveted form of contact: their cellphone numbers." News direct from the campaign has its advantages — it can provide access to the candidate and knowledge of campaign strategies — but it is also shaped by an agenda.

4. The Numbers Game

In the news networks’ ongoing competition to attract viewers, which in turn drives the money they make off advertising, debates play a key role. In the 2016 Republican primary debates, candidate Donald Trump, known for his controversial opinions and brash style, became seen as “ratings gold.” At a February debate hosted and broadcast by CNN, the network brought Trump back for two interviews immediately after the debate concluded. When Trump backed out of a March debate, Fox canceled the event altogether. Print, digital and broadcast news outlets have to sell themselves to the public and advertisers, which may shape their news judgment and coverage — and give popular subjects more control of the narrative.

- Why do some people complain that today’s news media is biased? Do you agree? Why or why not?

- When is bias in election news — from media organizations, the candidates or the public — a problem?

- Where do you get news about political campaigns or other important events? Why do you use these sources?

- What do you think is most important to consider when analyzing campaign information: who made it (source), why it was made (purpose), for whom it was made (audience), or how it was made (execution)? Explain.

Find three sources of information about one campaign issue, event or development. Review the content of the articles using NewseumED’s E.S.C.A.P.E. Junk News worksheet. Then, rate the bias of each source on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is completely unbiased and 10 is extremely biased. Write a paragraph or record a short video explaining your ratings by discussing the evidence, source, context, audience, purpose and execution of each article.

What’s your political personality type?

What’s your political personality type?

Make Your Voice Matter

Under 18 and can't vote?

Check out other ways to get involved.

-

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.1

Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.2

Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.6

Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.8

Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.1

Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively. -

Common Core State Standards: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.2

Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.

-

ISTE: 3b. Knowledge Constructor

Students evaluate the accuracy, perspective, credibility and relevance of information, media, data or other resources. -

ISTE: 7d. Global Collaborator

Students explore local and global issues and use collaborative technologies to investigate solutions.

-

National Center for History in the Schools: NCHS.Historical Thinking.3

A. Compare and contrast differing sets of ideas. B. Consider multiple perspectives. C. Analyze cause-and-effect relationships and multiple causation, including the importance of the individual, the influence of ideas. D. Draw comparisons across eras and regions in order to define enduring issues. E. Distinguish between unsupported expressions of opinion and informed hypotheses grounded in historical evidence. F. Compare competing historical narratives. G. Challenge arguments of historical inevitability. H. Hold interpretations of history as tentative. I. Evaluate major debates among historians. J. Hypothesize the influence of the past. -

National Center for History in the Schools: NCHS.Historical Thinking.4

A. Formulate historical questions. B. Obtain historical data from a variety of sources. C. Interrogate historical data. D. Identify the gaps in the available records, marshal contextual knowledge and perspectives of the time and place. E. Employ quantitative analysis. F. Support interpretations with historical evidence.

-

National Council of Teachers of English: NCTE.1

Students read a wide range of print and non-print texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works. -

National Council of Teachers of English: NCTE.12

Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

-

Center for Civic Education: CCE.II

A. What is the American idea of constitutional government? B. What are the distinctive characteristics of American society? C. What is American political culture? D. What values and principles are basic to American constitutional democracy? -

Center for Civic Education: CCE.IV

A. How is the world organized politically? B. How do the domestic politics and constitutional principles of the United States affect its relations with the world? C. How has the United States influenced other nations, and how have other nations influenced American politics and society?